The Kentucky Glass Works Company (also spelled “Kentucky Glassworks Company” within some contexts, such as contemporary newspaper articles) was incorporated in Louisville, as of July 23, 1879, with Edward Bull serving as president, William Cromey, secretary, and John Stanger, Sr., as superintendent. Within 5 months, Stanger had left the business and Henry C. Lentz of St. Louis, Missouri, replaced him, apparently holding the position of superintendent for the rest of the time the company was in operation. The factory employed a total of over 200 men and boys during it’s existence, although, at any one time, the number of workers might have been closer to 70 or 80.

The identification marks “KY. G. W.“, “K Y G W” and “KY.G.W.CO.” used on glassware made by this company are often mistakenly attributed to the original “Kentucky Glass Works”, which had operated in Louisville at the southeast corner of Clay & Franklin Streets from 1850 to about 1855 (known as the “Louisville Glass Works” from 1855-1873). In reality, the earlier Kentucky Glass Works of the 1850s did not mark ANY items with their initials, so far as I’ve been able to determine. (Some glass items from that earlier firm were marked “Louisville KY Glass Works”, that mark having been embossed on the front of several different types of liquor flasks, as well as on a very scarce early type of fruit jar.)

Because of the date range for these marks stated by Julian H. Toulouse (“1849-1855” in Bottle Makers and their Marks, 1971), which has been widely copied by a number of other writers in ensuing years (and even repeated to this day on some internet webpages), it is commonly believed by some collectors and historical archaeologists that the KY.G.W. marks date from that early period. However, a close study of various bottles embossed with these initials prove that they date from the 1880s, NOT the 1850s.

From ongoing research, I’ve found that this later factory operated in Louisville from 1879 (possibly actually starting production around September 1, since most bottle factories were closed during the months of July and August), to April of 1887 (being declared insolvent at that time). An appeal pertaining to a lawsuit (The Bell & Coggeshall Co., etc, v. Kentucky Glass-Works Co.) includes published material that seems to indicate the company shut down glass production on or about April 27, 1887. However, although it is possible that glass production continued somewhat later, I haven’t found any other documentation that would confirm exactly when the fires at the factory were extinguished for the last time.

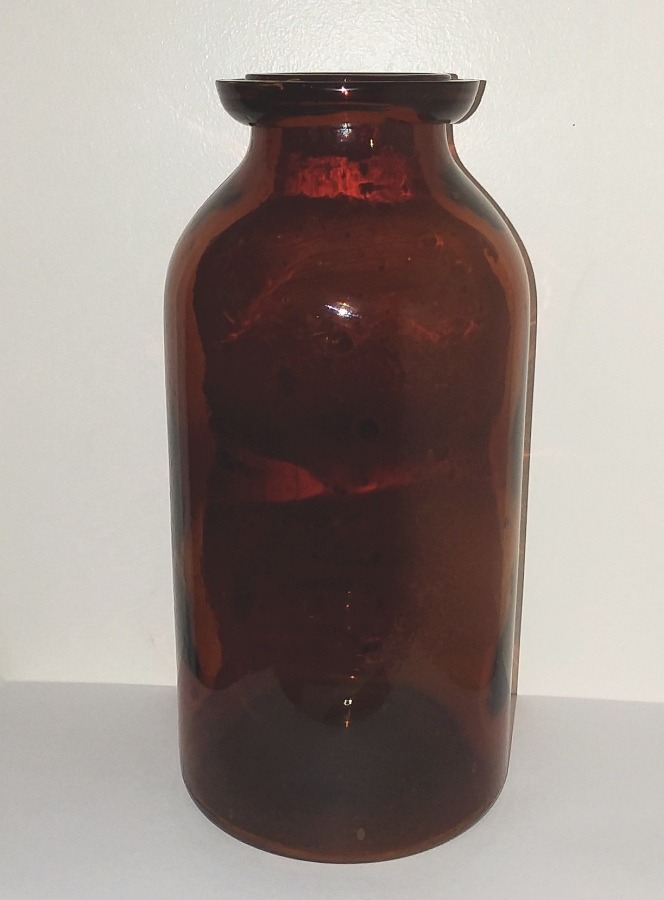

Several end-user companies that had bottles manufactured for them by KYGWCo were found to have been in operation only during the 1880s. The Kentucky Glass Works Company factory produced a large variety of utilitarian bottles and jars, including medicine, tonic, bitters, beer, ale, soda, mineral water, condiment, whiskey and pickle bottles; coffin or “shoofly” flasks (an example pictured on this page, marked KY.G.W.CO.) ; Wax Sealer style fruit jars; laundry bluing, Worcestershire sauce, & cylindrical chemical bottles (called “Druggists’ Packers” in some early factory catalogs), and many other generic utility and “general household” bottle types.

Much of the glassware made by this company is found in some shade of aquamarine (light to medium blueish-green) but there can be considerable variation in the exact shade and intensity of color from one bottle to another, depending on the amount of iron that was present in the sand used. The aqua bottles sometimes have streaks of amber or impurities “locked into” the glass. A lot of amber glass was also produced (such as beer and whiskey bottles), and the wax sealer fruit (canning) jars are found in a variety of colors including aqua, light green, citron green, dark red amber, yellow olive green and shades of light blue. There is no doubt that embossed private-mold bottles were made for local firms (such as Hutchinson soda bottles, patent medicines, etc.), but, in general, these cannot be positively identified as KYGW production without a glass mark on the base. From occasional newspaper items and ads, it is also apparent that KYGW made a standard array of common “stock” bottles (such as ale, wine, brandy, schnapps, etc) and some that were very likely unmarked, so identifying them would be difficult at best. A rare glass target ball is known that was made by this company.

The factory operated in (what was then) the south side of Louisville, located at the southwest corner of 4th Street and Avery (formerly known as “C” Street). This location is now a parking lot used by the University of Louisville.

Occasional factory worker strikes, as well as fires are recorded. Searching through newspapers of the era, I found that the Kentucky Glass Works Company factory suffered a damaging fire on Wednesday, January 26, 1881.

From the Louisville Commercial newspaper, Thursday, January 27, 1881, page 4: FIRE IN A FACTORY

“Injuries to the Kentucky Glassworks, which are fully covered by insurance.

“At 5:00 yesterday morning an alarm of fire was sounded from box 236, and soon afterward a second signal came, a lurid illumination appeared in the southern part of the city in the vicinity of Fourth Avenue, it being found by the firemen to be caused by a blaze from the outbuildings of the Kentucky Glassworks as far out as C Street. The buildings on fire were of such an inflammable nature that they were soon destroyed, though the engines were promptly on hand and did good work considering the difficulty of obtaining water.

ADVERTISEMENT

“The origin of the fire is a matter of doubt. It first started between the sand-drying and mixing rooms, and spread until the blacksmith shop, pot-house and several frame sheds were consumed. While the firemen could not save these buildings, they brought a heavy stream of water to bear upon the flames with such effect as to stay their progress. The factory and principal storehouse were unharmed.

“The loss by the fire is estimated at $10,000, including buildings and stock consumed. The pot-house was well filled with pots, only recently purchased, all of which were ruined. A lot of the beer bottles were destroyed, and considerable quantities of fire-clay and soda ash will be a total loss. The insurance on the property destroyed will amply cover the losses, as the following table will show:

Louisville…………………… $2483.00

Lamar………………………… $2483.00

Mercantile & Marine……………. $2483.00

Orient………………………. $983.00

Hoffman………………….. $983.00

Franklin…………………… $983.00. [Total, $10,398.00]

“Edward Bull, the President of the Kentucky Glass-Works Company, is virtually the owner of the property. The Superintendent says that the suspension of operations caused by the fire will be very brief, as the buildings consumed can be renewed readily. There will be no delay in filling orders.

The firemen have asked the Commercial to express their thanks to some lady in the vicinity of the fire, who kindly furnished them a good breakfast after the fire was over”.

Two other slightly different marks used by this company are “K.G.W.CO.” and “K. Y. G. Co.” They are less often encountered, and apparently were used on only a few types of bottles. At present, I can confirm that the “K.G.W.CO.” mark appears on the base of a blob-top quart amber beer bottle, and “K. Y. G. Co.” is seen on at least two sizes of aqua-colored coffin whiskey flasks, and a few cylindrical chemical bottles.

On another note, the earlier, unrelated Louisville Glass Works mentioned above (well known for several types of eagle, ribbed and scroll (“violin”) flasks they manufactured which are embossed “LOUISVILLE KY. // GLASS WORKS”), closed down in 1873, evidently as a result of the severe recession of that year, and never reopened.

Also, another company with a similar name (Louisville Plate Glass Works) was opened by John B. Ford in the Portland section of Louisville in 1874, but that concern evidently produced plate glass and mirrors, but not hollowware (containers). It operated there until around 1888, with frequent periods throughout those years during which the works were idle. Entries in Louisville city directories for the plate glass factory sometimes shortened the factory name to “Louisville Glass Works”, and this has confused researchers who assumed that this and the Louisville Glass Works of 1855-1873 were one and the same, which is incorrect.

Note: for a list of over 200 employees who worked at the Kentucky Glass Works Company factory during the 1879-1887 time period (extracted from city directories and census records) please check out my webpage here:

Kentucky Glass Works Company – list of employees

Other Louisville-area bottle glass factories operating in the late 19th century include: Southern Glass Works , Falls City Glass Company, and Star Glass Works, New Albany, Indiana.

Check out this link that points to an article about the original Kentucky Glass Works/Louisville Glass Works (1850-1855 / 1855-1873), which was published in Bottles & Extras magazine in 2005. This is “part one” of a three-part series of articles on Louisville glass factories of the 19th century.

Louisville Glass Factories of the 19th Century – Part One

See my home page here: Glass Bottle Marks – Home / Welcome Page

Glass Bottle Marks (Glass Manufacturers’ Marks on Bottles and other Glassware):

Click here to access “Page One” of the mark listings.

ADVERTISEMENT

I have just dug a broken aqua coffin flask marked K.Y.G.Co. I have most pieces and may have broke it myself. Is it really a rare find? It was only 2 feet down, have hopes of finding complete bottles, just thought i would share my find.

Hi, they are not common, but perhaps not extremely rare either. Because that type of flask has no marking on the face, (only the initials on the bottom) it would not be considered as “in demand” by the average bottle collector, so the value is not really high. Would you be able to send me a pic of the bottle? (or the pieces thereof), so I can see if it is similar or identical to ones I have. There are at least 3 different molds/sizes of this embossed coffin flasks with the exact marking “KY G Co” (as opposed to “KY G W” and “KY G W CO”). Thanks ~

David

Regarding the last picture on this page (Amber beer bottle), what do those 2 bumps on the base indicate? There does not seem to be a confident explanation anywhere and the most I can assume so far is that it is an indication as to what exactly the particular piece was meant to hold. I have definitely seen it on snuff bottles, but usually those have more than 2 bumps. I am currently in possession of an aqua base (very wide, likely a canning jar) from a trash pit that has 2 bumps (one on each side of the valve mark). Any knowledge about what these bumps indicate?

Hi Jessica,

This is a very interesting question and I don’t believe ANYONE is ABSOLUTELY sure what the answer is. However, here are some thoughts I’ll pass along…….

1) Some collectors believe that the “bumps” on the base of snuff jars indicated the strength of the snuff. I think that MIGHT have been originally true on very early snuff jars, as an easy way for snuff manufacturers (and purchasers) to keep track of which type/strength of snuff was in a particular jar if it all “looked the same” or if the label was missing or omitted. And in later years I am guessing it may have become just a “tradition” to make all snuff jars with the bumps even though they had gradually lost any and all real meaning either to the seller or consumer. It is possible the bumps were also merely a substitute for mold identifier numbers.

2) Concerning the KYGW amber beer bottle, I am fairly confident this is merely a mold identifier, and served as a substitute for the actual numeral “2”. It would have saved money and time for the mold engraver to just drill a “hole” or holes in the mold base plate to substitute for an actual number (numeral) which, of course, would require more skill, time and energy to properly and legibly engrave into the mold. I have also seen these bumps on the base of other Kentucky Glass Works Company bottles (such as shoofly [coffin] liquor flasks lettered “KY G Co” with one dot) and in that case I think it means “mold number one” on a particular size flask mold where more than one identical mold is being utilized.

3) Other bottles seen with bumps on the base….. “Whittemore / Boston / U. S. A.” shoe polish bottles are seen with various “dots” or bumps on the base. Since the bottles are the same size, but varying in number of dots— I have seen examples with one, two, or three bumps although higher numbers may be around— this could not be relating to the size/quantity/measure of the bottle, but most likely stands for a mold identifying number. I have noticed that on these bottles with the dots, there are no numerals present, and vice versa on the examples WITH actual engraved numerals.

4) I’m not sure about the canning jar but I am wondering if that jar was an example made on a particular type of automatic bottle making machine— do the bumps sorta look like the rounded side of a marble almost completely buried in the ground but with a small amount of surface showing above the ground surface?? My in-depth understanding of this type of mark is not good, but I THINK you are describing a jar made on one of the very early types of jar machines called the BALL-BINGHAM semi-automatic machine. Please see this link and look at all the pics farther down on this page……….

Ball Bingham Machine- Ball Jar Collectors Community Center Discussion Forum.

In summary, I think the bumps on bottles had more than one purpose, and it depends on exact WHAT type of container is being discussed. (This discussion is only relating to early glass bottles…….NOT bumps or dots seen on recent, modern-day, present-day containers which is a whole different ball of wax!!! …… See my page here with a brief mention, near the base of page, concerning dots on modern-day bottles…….).

Numbers seen on the bases of bottles.

I hope this helps a bit,

Take care, David

Thanks for the reply! I’m working on my Master’s work on a ranch in Texas and I’m currently working on the surface layer of a homestead. The particular base I referred to in my previous comment is associated with several other pieces from a trash pit that I’ve estimated were in use in the 1930s. However, there is one piece that looks to be much earlier (a light green ink bottle) that could have been in use for a long time. I will be excavating the trash pit soon enough to see how far back it extends, but I have to complete survey on the rest of the land first. I have noticed several broken bases with bumps on other parts of the land (and yes, they have the buried marble look that you described) and could find no more information other than its association (maybe) with a mold. A lot of them look like old snuff bottles, but I have seen many wider, round bases of clear and aqua glass with anywhere from 2-4 bumps on the bottom (assuming canning jars, but without the rest of the jar, it’s a guess at this point – but that’s archaeology haha). I thank you for your link on the semi-auto machine. I have some material that covers the surface of semi-automatic vs. automatic, but I have yet to start researching it in-depth.

I’m just getting into the fieldwork on this 209-acre ranch, so don’t be surprised if I send you another comment over the next few months!

Thanks!

Jessica

Thanx Jessica ~~ Feel free to submit comments anytime!

David