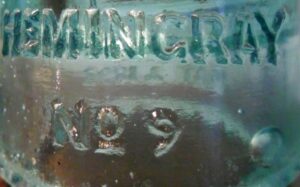

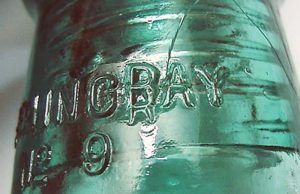

“HEMINGRAY No 9 // PATENT MAY 2 1893”

Marking embossed on Glass “Pony” style telephone insulators

Embossing index [250]

“Pony” insulators are smaller types usually installed on low-voltage telephone lines. They were used in large numbers on rural communication lines as well as short-distance lines within towns and cities. Pony insulators were made by a number of glass companies, including Hemingray, Brookfield, Ohio Valley Glass Company, California, Lynchburg, and others, and are found with a wide variety of embossed markings. One of the most common types of pony insulators was made by Hemingray Glass Company of Muncie, Indiana, and that was their “Number 9” style.

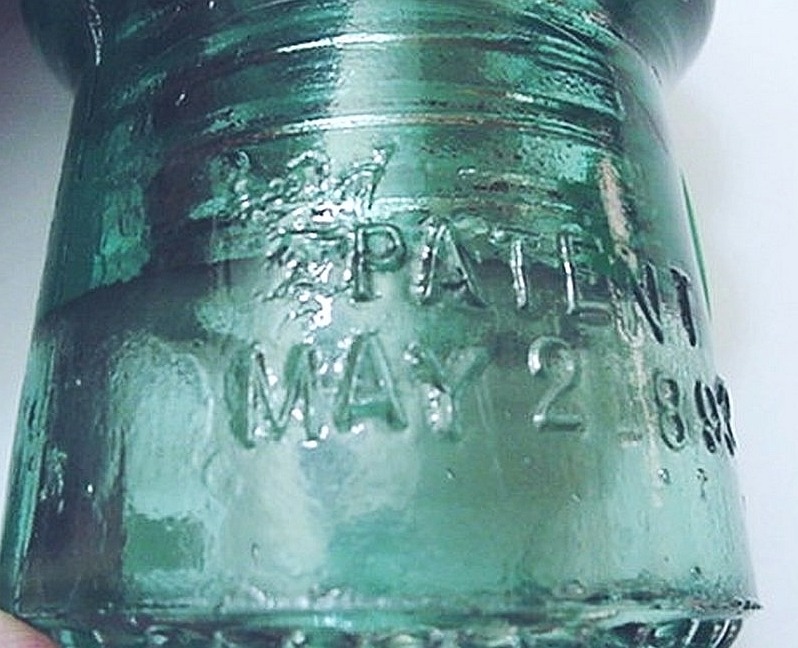

Although no one is sure just when the first “HEMINGRAY NO. 9” insulators were made, they are believed by some researchers to have been made beginning about 1892, a short time before the patent for drip points was issued on May 2, 1893. A few examples are found with a smooth base, lettered only “HEMINGRAY / No 9” on one side, and those are thought to be the very first No. 9’s made, shortly before the 1893 patent officially went into effect. Some of those same molds exist in both smooth-base versions and a version with sharp drip points and the “May 2, 1893” embossed lettering.

The May 2, 1893 patent referred to the addition of the “drip points” (teeth) along the base rim of the insulator which were touted as an improvement on helping the insulators do their job on electrical lines – helping the rainwater to drip off the insulators and away from the wires. The effectiveness of this invention is highly questionable after all these years, but the patent was certainly “hyped” to a great degree by Hemingray. A large percentage of their insulators were made with drip points for many years.

Most of the Hemingray No. 9 insulators were made at the Muncie factory (which had begun glassmaking in 1888) but it appears that their first factory location (at Covington, Kentucky, where business offices remained until 1919) was reopened for some period of time, perhaps 1900-1902, and quantities of the No. 9s were also made there. Judging from shards found along the Ohio River riverfront area, most of the Number 9s made at Covington appear in shades of light blue or blue-aqua, often with lots of bubbles, and are of the “Prismic” embossing variety.

ADVERTISEMENT

Many Hemingray NO 9 embossing variations were made over the years. The Hemingray NO. 9 pony style (classed as a CD 106 in the “Consolidated Design” system of identification introduced by N. R. “Woody” Woodward) was made for about 63 years (1892-1955), making it the longest running style of glass insulator ever made by Hemingray Glass Company. The “42 and the “9” are the two most common glass insulators ever made by Hemingray, but there is uncertainty about which one should be placed in the “Number One” position in reference to total numbers made.

Although many different embossing variants are known, including later variants that were made up to 1955, this article will concentrate on the most common Hemingray 9 embossing variant………… the type known under the “EIN” (Embossing index number) #250, which is written as [250] in the McDougald and Briel glass pintype insulator price guides used by most experienced collectors. The [250] index is lettered “HEMINGRAY / No 9” on the front skirt and “PATENT / MAY 2 1893” on the rear skirt.

A few of the [250] related error molds are listed in the price guide under a different EIN, such as the “HEMINGAY” mold spelling error, which is listed as EIN [060] .

Please Note: Other lettering variants that post-date the [250] embossing type include:

HEMINGRAY / No. 9 // PATENTED / MAY 2 1893 (Estimated Production Date: 1909-1912)

HEMINGRAY / No 9 // PATENTED (E P D: 1911-1912)

HEMINGRAY // No 9 (E P D: 1912-1919)

HEMINGRAY-9 // MADE IN U.S.A. (E P D: 1919-1933)

HEMINGRAY-9 // MADE IN U.S.A. [along with with mold and date code numbers] (E P D: 1933-1955)

There are also a number of other, slightly different embossing variants to be found.

This style of insulator was widely distributed across the United States, being used almost everywhere, and can be found in virtually every state in the country. However, I seem to notice these are more frequently found in the Midwestern and Western states, and less so in the Northeastern, East Coast and Mid-Atlantic states. I would assume this was because of Hemingray’s fierce competition with Brookfield Glass Company, of Brooklyn, New York, the latter which supplied tremendous quantities of pony insulators to the Eastern part of the country (as well as the rest of the country) during that time period.

EMBOSSING TYPES

WITHIN THE [250] EMBOSSING, there were several different “font” or embossing styles used for the lettering. They are generally known as (1) “Script” (about 1892-1894), (2)”Evo” (a short-lived transition between Script and Prismic styles, with 2 sub-variants, circa 1894-1895) (3) “Prism”, “Prismic” or “Prismatic” (circa 1895-c. 1901) and (4) “Type”, “Typewriter” or (now, more commonly known as) the “Stamp” style embossing (c.1900-c.1910).

This same general succession of font types may be recognized on some other insulator styles made by Hemingray, including the CD 113 (Hemingray No. 12), which is closely related in size and style, but is a “transposition” type bearing two wire grooves instead of one. The No. 12 was often used on telephone “drop lines” extending from the back alley to individual homes and businesses.

This [250] embossing has been found in a wide variety of glass colors, although a few of the more “exotic” bright colors (ambers, cobalt blue) as seen on some other Hemingray insulators such as the CD 162 signal style used on power lines, are virtually unknown on the Hemingray NO. 9.

The Script embossing has a comparatively lightly-embossed quality about the lettering. The “1893” date is typically crude with a noticeably “handwritten” appearance.

The “Prismic” embossing tends to have a more angular look to the letters, with sharper corners and a crisp, “cut” higher-relief prism-like appearance in evidence. Within the Prismic embossing, there are two main varieties of the number “2” including the “Looped” or “Cursive” 2, and the “Swan” style 2. On most of the examples with the “Looped 2”, though not all, the embossing tends to be rather small. These two varieties of the “2” are believed to reflect the work of two different mold engravers.

ADVERTISEMENT

As is true of most glass insulators of this earlier era, the great majority are found in shades of aqua (blue-green). The earlier Script colors include, besides typical aqua and light aqua, a range of pastel tints. Here is a general color list, although I must make it clear it is NOT definitive or comprehensive! There are other ‘tweener’ colors that cannot be easily described. Color names used by one collector may not describe exactly the same shade as the same color term being used by someone else.

Colors seen on the “Script” embossing style include: aqua, light blue aqua; aqua tint; ice aqua; sky blue; medium blue; lemon tint; light cornflower blue, ice green; light green aqua; light green; medium green; Depression Glass green; gray; sage green; crystal clear (like Pyrex); clear and off-clear.

Collector and pony specialist Brent Burger states “If a “PATENT DEC 19 1871″ [embossed insulator] can be found in a given color, chances are a Script No.9 can, as well.”

“EVO” style embossings, which are rather hard to find, have been seen in most of the same colors as the “Script” style. “EVO 1” can be identified by the oddly shaped “9”, shown here. It bears a vague resemblance to the Bass Clef sign as used in sheet music. The engraving in the molds was deep and the resultant embossing on the insulators is strong and bold.

The “EVO 2” is a seldom-seen variant which is more lightly engraved, the lettering with rather squared-off orientation and similar to the succeeding Prismic style.

Prismic style colors include: aqua; light aqua; bubbly aqua; light blue aqua; ice blue; medium blue; dark blue; heavily bubbled blue; snowy “blizzard”blue; snowy “blizzard” aqua; Hemingray Blue; ice green; light green; medium green; jade green; jade blue; mustard olive; yellow green; dark yellow green; dark green; olive green; clear and off-clear.

Some of the colors in these earlier embossing variants are very scarce to rare, and in some cases nearly impossible to find.

STAMP EMBOSSING VARIANT

The “STAMP” embossing was created by the mold engraver actually ‘stamping’ the individual characters (letters, numbers and punctuation) backward one at a time into the inside surface of the insulator mold, apparently using small individual punches or “letter stamps” and a small hammer.

This article is primarily about the stamp style [250] which was, according to the best estimates by collectors and researchers, made from around 1900 to circa 1909-1910. Untold millions of insulators in this style were manufactured. This coincided with a time period when many, many small telephone companies were being formed left and right, and huge numbers of pony insulators were needed for the expanding networks of telephone lines across the United States.

(Around 1910 the word PATENT was changed to “PATENTED” on the new molds. There were evidently some changes in the molds or molding process around that same time, as a close examination of the PATENT versus PATENTED molds will show that, in the great majority of cases of the PATENT molds, the threading (and resultant thicker glass) extends farther down toward the base of the insulator than on the PATENTED examples. With a little practice, the PATENT and PATENTED versions can usually be differentiated from several feet away, if one can clearly see the vertical extent of the threading.)

Many of the “STAMP” embossed molds were re-machined after some unknown period of time, which resulted in varying widths. By comparing multiple mold examples, it is clear that if a mold was machined (re-tooled, actually grinding away some of the metal from the inside of the mold, primarily in the area of the wire ridges), the resulting mold cavity was made slightly larger, resulting in a wider, heavier insulator.

These larger Hemingray No. 9s are known under several nicknames, such as the “WIDE DOME”, “BIG HEAD”, “FAT BOY” or “FAT HEAD” type. Some of them are considerably thicker and heavier than their narrower “mold twins”.

By far, the great majority of the “STAMP” units are found in a characteristic medium aqua, but some are found in green aqua; Hemingray Blue; light blue; snowy light blue; milky swirled aqua, jade green milk or “jade aqua” (which might be called a milky, translucent or foggy greenish-aqua color); light green; sage aqua; sage green; lavender; light lavender; purple; light purple; gray; grayish purple, and a gray/purple mix. Some examples are found with splotches, streaks or swirls of amber. Nearly all have at least a few bubbles embedded in the glass, sometimes many bubbles of various sizes.

The [250] “Stamp” embossing style exhibits a number of errors, including instances where one letter was stamped over another in the mold. There are many molds where the arrangement of the letters and numbers are FAR out of alignment, presenting an erratic or “jumpy” appearance.

ADVERTISEMENT

In some cases an individual letter leans strongly to the right or the left, is higher or lower than an adjoining character, or is too close or too far apart from the next letter in sequence. Sometimes a letter in the top line of text is virtually touching a letter in the line below.

There are at least 3 “STAMP” molds (and very possibly more) where the “A” in May does not have a crossbar. In actuality, this A appears to be merely an upside-down V which was used by the mold worker. Apparently he intentionally or accidentally stamped a “V” stamp into the mold instead of an A. Since it occurs on at least 3 molds, this would seem to have been done intentionally. Perhaps he had misplaced his “A” stamp?

Other errors include the “HEMINGAY” misspelling error; a mold in which the name is spelled “HEMIGRAY“; a mold in which the “8” is double-struck; another mold in which the “R” is stamped twice; as well as a mold in which the “9” is double-stamped. In at least one mold, the “9” under the name HEMINGRAY is actually an upside-down “G” stamp. Another variant has a letter “M” placed to the left of “No 9”, probably resulting from the mold worker starting to engrave “MAY” on the second line, and then realizing his error.

On one very distinctive mold, a weird image appears to the left of the letter “P” in “PATENT”, looking vaguely similar to a bird with outstretched wings, or perhaps an abstract “angel”? Exactly why this mold anomaly occurred is a question I have!

A scarcer sub-variant of the “STAMP” style embossing bears lettering that tends to be lightly embossed and have characters with “thinner” weaker strokes as if the letters had been more lightly “traced” in the mold. Some of the characters (especially the “2”) always seem to lean slightly backward (to the left). The “E” is slightly narrower. Some examples of this particular type have a vaguely ‘cruder’ look, sometimes with a faint sage green cast to the aqua color. A few of these bear almost illegible embossing, sometimes with a crude ‘washboard’ surface texture. I know of one shard of this embossing type found along the Ohio River at Covington, so I suspect at least some of the insulators produced from those molds are products of the Covington factory, which would date them to around 1900-1902.

!["HEMINGAY / NO 9" error. This is listed as index [060]. There was evidently only one No. 9 mold with this particular engraving error. The other side also has an error: The "P" in "PATENT" was stamped over an "H". Hemingray No. 9 insulator -- "HEMINGAY" error. This is listed as [060]. There was evidently only one mold with this engraving error.](https://glassbottlemarks.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Hemingay-error-CD-106-aqua-resized-222x300.jpg)

Although no one knows exactly how many different STAMP style [250] molds were made and used during their (approximately) ten-year period of production, presently I’m estimating the TOTAL number of “Stamp” molds to range somewhere between 500 and 600.

Although it might seem to be a formidable task to compare the embossed lettering on these insulators to determine if any particular example is a “mold twin” to another one in someone’s collection, especially if you have a large number of units, it is actually fairly simple, if somewhat time-consuming, to do, if a few steps in my method of identification are followed. The “Stamp” molds are (in most cases) easier to tell apart from each other than the Prism molds are, simply because of the often erratic placement of the stamped letters. The mold engraver had great difficulty in stamping the characters in EXACTLY the same position from mold to mold.

Because of the erratic nature of the stamped letters, no two “STAMP” molds within the [250] index are absolutely identical……… each mold can be individually identified under close scrutiny. For instance, there is considerable variability in the positioning of the “9” under the name Hemingray. It may be found positioned directly under “IN”, “N”, “NG”, “G”, “GR”, “R”, “RA” or “A”. In some cases the 9 is positioned slightly to the right or left, such as “slightly to the right of the letter G”. So far, I have only seen one mold where the “9” is positioned directly under the “A”. I know of only three examples from that one mold.

The most common placement is below the “G” or slightly to the right or left of the G. Incidentally, a number of the purple colored units (and some of the light pastel green units) are from molds in which the “9” is positioned underneath “IN” or “N”.

Thus, by grouping [250] molds into several groups, beginning with determining the position of the number 9 under Hemingray, further characteristics of the lettering orientation (on both sides of the insulator) can be studied to determine if the mold is a “new” or different one as compared to others in a collection or accumulation. For instance, does the vertical stroke of the “P” in “PATENT” line up exactly with the top of the “A” in “MAY”?

And by eyeballing the position of the “T” in relation to the numbers below: does the vertical stroke of the second “T” in “PATENT” line up directly with the 1? The 8? Or the 9? The 3? Or somewhere in between? Does the “I” in HEMINGRAY point directly down towards the “o”? Or maybe it points toward the “N” in “No”? Is there any unusual spacing of any of the letters or numbers readily apparent?

If there are other numbers or letter out of alignment, note that and carefully compare with other examples to see if they are placed in the exact same position. If they are, go on to another character and keep looking for exact matches in orientation relative to each other.

ADVERTISEMENT

There are three different styles of the letter “G” seen on the STAMP style No. 9s. One variant has a very slightly narrower “bottom loop”, as if approaching on a “V” shape. The second type is the most common, seen on probably 70% or more of these units. The short horizontal stroke of this G usually looks indistinct or “sloppy”. The third type of “G”, which I am fairly sure is the last version used on the [250] embossing, is the same “G” which, for reference, looks a little bit wider or “rounder”, is more well-formed, and is the type of G seen on virtually all Hemingray No. 40 insulators, as well as all of the No. 9 insulators with the word PATENTED instead of PATENT.

When looking at a few examples of these insulators, in a random assortment there may be no duplicate molds at all — each piece exhibiting lettering noticeably different from the others in alignment and spacing. Yet, in another small accumulation, several mold duplicates might be discovered. Sometimes this is because the insulators were taken down from one particular telephone line where they had been installed close to each other from “day one”, and in fact had been in relatively close proximity their whole “life”- from the time they were made from a particular mold, removed from the lehr, packed, shipped, installed on a line, and, many decades later, removed from service and placed together in a bucket when the line was upgraded or dismantled.

Examining a number of these units and trying to find “mold twins” is something only true “insulator nerds” might do, but that would probably describe myself! I tend to compare this to the eccentricities of the numismatics (coin collecting) fraternity that sometimes goes (what may seem like) a little overboard on studying many very slight variations in coin dies, as seen under a microscope or loupe.

I hope this article will help some new, beginning, (and older) insulator collectors gain a new perspective on the Hemingray NO. 9 style that served on telephone lines for so long here in the United States.

(Thanks to CD 106 specialists Brent Burger and Kim Borgman for their emails with insight on colors seen on the Script and Prism style insulators!!)

LINKS to some other webpages within this site:

GLASS BOTTLE MARKS website Home / Welcome Page

General Overview on Glass Insulators

California Glass Insulator Company

List of Glass Manufacturers’ Marks on Bottles, Insulators and Tableware (alphabetically arranged)

Insulators.info “Picture Poster” photo gallery pages ………… You can browse (and search with specific keywords) this picture gallery where thousands of insulator photos have been posted over the last 20+ years, including pieces made by Hemingray and other glass insulator companies.

Insulators.info – Photo Gallery – over 20 years of photographs archived!

Here’s a webpage on the No. 9 style, from Christian Willis’ site about Hemingray insulators: Hemingray CD 106 – Hemingray.info

Here is an article written by John McDougald, and published in “Crown Jewels of the Wire” magazine in 2001. Pictures of many CD 106 Hemingray 9 variants are shown.

Hemingray No. 9 – CD 106 – John McDougald Article – CJOW.com

ADVERTISEMENT

It doesn’t say in the articles about the No.9 being positioned on the opposite side of the insulator..

Hi William,

I’m sorry but this article is primarily about the oldest main type of “No 9” insulator which is classified in the price guides as embossing index number [250]. There are a number of other variants, including the type with the “No. 9” embossed on the reverse of the insulator. I do list that embossing variation, along with several other major variants, in about the seventh paragraph down in this article. I haven’t tried to go into detail about the later, newer types of the Hemingray NO. 9. This is partly because I am a little less interested in them because they are newer, but also because of lack of detailed information, and of time, energy and patience in researching them.

Perhaps someone else can explore those variants and come up with better background information in the future. There are already several other articles that can be found online about the various Hemingray number 9 types (CD 106). One article was written by John McDougald many years ago, and was published in the Crown Jewels of the Wire magazine. It is also posted on the web.

Thanks for writing,

David